Over at The Chronicle Review, Camille Paglia stirred quite a few pots a while back by asserting that George Lucas might be the greatest artist of our time. It’s no surprise that your average appreciator is having a hard time with that statement, for a veritable walk-in closet’s worth of reasons. But I found myself won over by her argument in many places, particularly where she pointed to George Lucas’ myriad of influences and the fact that he is a primarily visual artist.

Which is when I decided to watch the Star Wars prequels with the sound off.

Love or loathe them, the Star Wars prequels are undoubtedly the blemish that has made Lucas’ name snicker-worthy for more than a decade now. Even if you’re a prequels apologist, there are certain elements of those three films that simply cannot be reckoned with by the light of day; the dialogue is depressingly trite and repetitive, the plot of the whole trilogy becomes incoherent 30 minutes into Episode I, and strange bits of retcon Lucas has since added to the original Star Wars films to smooth out the wrinkles leave most fans at a loss.

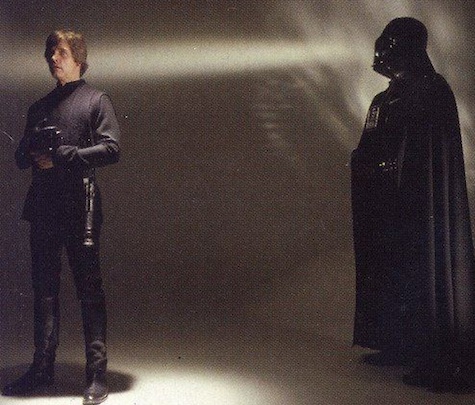

Then again, the dialogue of the first Star Wars trilogy is anything but poetry. The plots are easier to understand, but then again, the arc of those films is far more manageable than anything explored in the prequels: boy wants to know “dead” father, gets the chance to learn father’s trade, joins rebellion to overthrow tyranny, finds out dad is among the tyrant’s number, finds his sister, redeems dad, restores balance to the galaxy. It’s pretty Greek to me… and by that, I mean it sounds like a Greek comedy. Or maybe a Shakespearean one. Or a piece of Japanese theater.

Lucas has proved with every Star Wars film that what he is most interested in doing is meshing different elements of history, mythology and art into one big world stew. The basics of the Star Wars universe owe a lot to western mythology and Eastern religions and films, certainly, but there are hints that point to a vast encyclopedia of outside sources. There were Saturday matinees with Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon, comic books, art films by Fellini and Godard, dystopian science fiction, the drag race culture of the 1950s, and so much more. As though Lucas spent his youth absorbing everything he could, in an effort to combine the world’s storytelling efforts into one giant behemoth of super-culture. The charm of the original Star Wars trilogy is its simplicity. Its structure and tropes feel like they could have come from anywhere, at any time.

As Paglia expands upon, Lucas referred to his student films as “abstract visual tone poems” (which, if you’ve ever seen the student film version of THX-1138, is hard to dispute). So what if Star Wars was simply building on that sensibility? Building out and up, but not in a way that today’s culture finds acceptable? Because the Star Wars prequels are not what general audiences like these days. We like drama, sharp dialogue and complex plotting, and only when they pan out—many fans of LOST, Battlestar Galactica, or Nolan’s Batman trilogy will attest to the disappointment that ricochets when a beloved story lets them down. But George Lucas has never really cared about dialogue; Paglia points out that he has been known to call it “a sound effect, a rhythm, a vocal chorus in the overall soundtrack,” of a film. The script is “a sketchbook” and he’s “not really interested in plots.” And to most of us that surely sounds like madness. But to George Lucas, who considers film to be an entirely visual medium, it’s exactly right.

By that notion, one could eliminate the most problematic aspect of the prequels and watch them all over again for that visual experience. With the soundtrack playing, preferably, as the appointment of John Williams as the composer of these films was a very deliberate choice on Lucas’ part.

So, what do they look like? Well, here are some impressions from my own viewing….

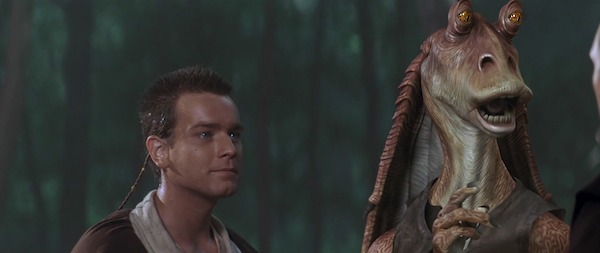

I’ll admit, there’s very little to save Episode I. Even with the sound turned off, the movie amounts to a lot of standing around interspersed with some incredible action sequences, especially at the beginning. Jar Jar is far less irritating when you don’t hear him, a slapstick vaudeville-looking creature with the whole schtick down pat. Because Jake Lloyd’s performance is the performance of a very young child, it’s hard to get a read on Anakin through the whole film; on silent, I almost wish he would camp it up so I could figure out how he’s feeling. The scenes with his mother are always the most telling. The visual cues delivered by Padmé’s costumes become far more clear—each color carefully chosen, each silhouette conveying a different emotion or persona.

The final duel between Obi-Wan, Qui-Gon and Darth Maul is just as effective as it ever was, perhaps more because we don’t need to hear Qui-Gon’s final request. It is hardly surprising that lightsaber fight techniques were overhauled for the prequels; if Lucas could make use of more than one style, allow for fencing, acrobatic, and martial arts techniques, it would only absorb more cultural reference points into his operatic collage. The visual symmetry of the Episode I’s finale against A New Hope’s medal ceremony is still a bit off-putting with the celebration music (one of Williams’ few missteps in my opinion), but it’s more ominous when we know what direction this story must go.

Onto Episode II… where the visuals are much clearer in terms of how they’re wrangling your emotions. The death of Padmé’s decoy out of the gate is a deliberate kick, a warning about the ever-downward spiral that these films become. Everyone seems much more sinister without hearing their dialogue, particularly Anakin, interestingly enough. The way his often wooden expressions change when he’s angry or sly is actually a bit terrifying. Obi-Wan is very clearly occupying the place of comic relief here, and I can’t help but wonder if his ridiculous haircut isn’t a part of it. The lights of Coruscant’s underworld districts invoke a bizarre echo of Blade Runner, but even trashier, more Vegas, which makes perfect sense.

The hardest thing to keep track of watching Episode II is the multitude of characters and how they all finally come together in the end. In addition, Lucas’ desire for visual symmetry often muddies the story; Anakin gets his arm cut off because Luke got his hand cut off in the middle chapter of the original trilogy. Visually, this retracing makes sense. Yet in Empire, Luke receives that wound as a teaching tool of sorts, reminding him that he made a mistake in chosing to face Vader ahead of time. It happens often in mythological yarns, the hero bearing a physical wound as a reminder of past failures or important lessons. (Frodo loses a finger due to his failure letting go of the Ring, Harry Potter bears the scar from Voldermort’s curse to remind him of his mother’s love and sacrifice.) But Anakin’s wound seems less meaningful—he has just lost his mother, and is worried that he might have lost Padmé as well; he is not thinking clearly, and his pain is ignored by everyone surrounding him because they are unaware of his recent trip to Tatooine. In addition, the loss of that arm teaches Anakin nothing that we are made aware of. It makes all visual cues dealing with the severed arm feel forced, unearned.

The love story, which has always received most of the ire from fans, is practically inoffensive this way. As I mentioned before, there’s a Greek or Shakespearean quality to it, perfect for silent film: people turning to each other and away again, smiling and touching, arguing and pleading. The costume changes for Padmé again let us know so much about her—when’s she’s feeling flirtatious, whimsical, or sexual. Without the specific dialogue problems, it’s much easier to connect with the couple. And when accompanied by John Williams’ patently epic theme “Love Across the Stars,” the emotion is right there for us to reach out and grab hold of.

And then the final chapter, Episode III. What’s shocking about watching this film without sound is how it visually conveys darkness closing in, limits the color palette of the first two films entirely, and seems intent on frightening you. The lingering on Anakin’s forced happiness at the thought of children and that first hazy dream of Padmé in unbearable pain, it’s like some gothic nightmare unfolding galaxies over. Compare the ships in Phantom Menace to Revenge of the Sith—we’ve gone from silvers and yellows to black and gray. Sleek elegance has been traded for sharp lines and shadowy corners. Forget the physics of it, this is meant to be a subconscious mass of clues. It’s almost Tolkien-esque in its arc, the cold metal clang of progress striding out ahead of natural beauty and creative venturing. Padmé comes from Naboo for a reason, a representative of old ways that will soon be destroyed by the Empire: refinement, political and artistic awareness and, especially, compassion. The fact that she maintains this, even as Anakin is fighting a war, even as his dogmatic views begin to destroy him, is all part of the puzzle.

The execution of Order 66 (which I have always found emotionally affecting, regardless) is staggering. Wave upon wave of troopers, young children fighting for their lives and failing, bodies collected on the ground, all of these elements linger when no one is speaking. Obi-Wan’s grief at losing Anakin is acute, rather than dispersed by empty lines about whether or not he can kill him, how he must stop him, who is meant to bring balance to the Force. Certain sections are still overreaching—the fight between the Emperor and Yoda fails to come across as either important or moving, but it occurred to me that it’s probably due to the location; holding it in the Jedi Temple, having Yoda fight to defend his territory and home from evil, would have likely been much more affecting.

In her article, Paglia clarifies the ways in which the final duel between Anakin and Obi-Wan represents a descent into Hell, the sort that renaissance painters had to capture image by image over so many years. Instead, George Lucas offers it all in one go, circle by circle as the station on Mustafar falls apart. We then move on to one of the great sci-fi nightmares, watching from Anakin’s own point of view as he is sealed forever inside a suit, maintained by machines that see and breathe for him. A monster of invention now, and without that ridiculous call of “No” that seemed to go on forever in the film, you can decide for yourself what he’s saying. Perhaps “Why?” or “Let me go” or even silence—a pose of supplication on Vader’s behalf, the futuristic image of a tortured robot saint.

The experience, all in all, is something entirely different. It doesn’t tighten up the story at all, nor does it give the universe the same “used car” look and feel that the original trilogy had, but it does play on a distinctly different emotional level. It’s probable that watching on mute still won’t do it for anyone—we don’t exactly appreciate silent films the way we used to as a culture (no matter how much I love Buster Keaton), and they’re not likely to make a comeback any time soon. But it made me feel as though I understood what George Lucas was going for. And even with the many layers of CGI, it cannot be denied that these movies are visually unique in a way that no one else ever matched. No one builds on Lucas’ scale. Because they can’t manage it or they don’t want to try, it doesn’t really matter either way.

Or, to put it another way—if some distant race from another planet got their hands on the Star Wars prequels with no foreknowledge… imagine how incredible that would look to fresh eyes. While “greatest artist of our time” might be hyperbolic, that doesn’t mean that the prequels have no artistic value whatsoever. Perhaps they just need to be viewed through a different lens. As “abstract tone poems” go, I’ll cop to being impressed.

Emmet Asher-Perrin thinks that twin sunset will always be one of the best things ever captured on film. You can bug her on Twitter and read more of her work here and elsewhere.